Chinese emperor Huizong (from the Song dynasty) reportedly once said: “Teas vary as much in appearance as the different faces of men.” I actually couldn’t agree more. When I first came to China, though, I knew little enough about teas in general and even less about Chinese teas in particular.

But after years in China and hours of sitting, brewing, sipping, enjoying, and learning about different kinds of teas, I have gained a deeper understanding of the different teas here. A friend of mine has a tea shop in Shenyang’s 温州城 (wēnzhōu chéng in pinyin, Wenzhou City in English). She has helped educate me more in this ancient Chinese tradition. And every time I go visit her, minutes turn into hours when she lets me try new varieties or special editions she finds on her frequent trips to tea plantations and fairs.

Tea has been grown and consumed in China for thousands of years. In Yunnan province of China is what researchers believe is the oldest still existing cultivated tea tree. It is 3,200 years old! The earliest surviving records speak of tea consumption during the Shang dynasty, in the second millennium BC. And archaeologists found tea leaves on a dig that date from the Han dynasty. From the second century BC, to be exact. Not sure whether that tea would still taste good today, though.

Not only does China have an astonishingly long history of tea culture, but the variety of teas is surprising as well. Green tea, Oolong, Black and Pu’er Tea all come from the same type of plant, called camellia sinensis, the tea shrub. The technique used after picking the leaves then determines which kind of tea you end up with.

Let’s have a look at some of the different types of tea, shall we?

Green Tea

The first kind of tea you think of in connection to China is probably green tea. Many people are actually unaware of the other types of Chinese tea, they believe that green tea is all people drink here. That is far from the truth. But green tea is still one of the more popular choices when the Chinese are brewing themselves a cup.

Green tea has the simplest production method out of all the varieties discussed here: the tea leaves are plucked from the shrub, then dried (by sun-drying, charcoal- or pan-firing, oven-drying, or other methods). That’s all. Sounds simple, right? But there is still considerable skill and knowledge that goes into the production of famous green teas.

Arguably the most renowned Chinese green tea is Dragon Well Tea (龙井茶 in Mandarin, lóngjǐng chá in pinyin). The loose tea is light green in color, with individual, flat crumpled leaves. And the resulting tea has a light, slightly bitter taste to it.

Chinese tea is never just steeped once. Actually, the first brew is merely used to wash out the teapot and cups, then thrown away. For a good quality green tea, the recommended number of brews is 3-5 times maximum.

Green tea is a summer drink in China, since – according to Chinese medicine – it is a cooling drink. So, having green tea in winter is not considered healthy. But never fear, there are a lot of other options out there that work even during our current season of perpetual darkness and sub-arctic temperatures.

Jasmine Tea

Jasmine tea is not really its own variety, but merely green tea (or, more rarely, black tea) that has been scented with jasmine flowers. The tea leaves are picked in the spring (during the first tea harvest, when you get the best leaves), then kept refrigerated until late summer, when the jasmine starts to bloom. The jasmine flowers need to be picked at daybreak when their small petals are still tightly closed. They will be kept in the cold and dark until late in the day, then mixed with the dried tea leaves. During the night, the jasmine releases its scent and infuses the tea leaves with its sweet and flowery fragrance. Depending on the quality of the tea, this scenting process can be repeated several times, until the desired intensity is acquired.

Jasmine tea is brewed similarly to ‘normal’ green tea. Its color is similar to that of green tea, but it smells strongly of the jasmine flower. Jasmine tea purportedly has health benefits to those who drink it regularly, because of the antioxidants contained in it. But again, not during winter.

Oolong Tea

If we slowly journey from light to dark, the next stop on our tea journey would be oolong tea (乌龙茶 in Chinese, wūlóng chá in pinyin). This slightly darker tea – mostly greenish-yellow to light-brown when brewed – not only sports many different looks but also offers a wide array of flavors. Teas that fall within the oolong family are all half-oxidized, but since the degree of oxidization can be anywhere between 5 and 85%, this allows for vast differences in appearance and flavor.

Tie Guan Yin and Da Hong Pao

My two favorite oolong teas are Tie Guan Yin (铁观音 in Mandarin, tiě guānyīn in pinyin) and Da Hong Pao (大红袍 in Chinese, dà hóng páo in pinyin).

Tie Guan Yin is so lightly oxidized it can almost pass for a green tea. The remarkable thing about this tea, in addition to its fresh taste and beautiful color, is that the tea leaves are rolled into little individual balls. This is where this tea takes its English name: gunpowder tea. Making this tea is a lot more involved than green tea. In total, 8 steps are needed to produce it. First, the tea leaves are plucked, then they are withered in the sun. Then they need to cool, before they are tossed, and withered again. In this second withering step, the oxidation takes place. Then, the tea is fixated, rolled, and finally dried. With all of this labor, it is understandable that Tie Guan Yin does not come cheap. In fact, it is among the most expensive tea on the world market.

Da Hong Pao is on the opposite spectrum of the oolong tea. A heavily-oxidized oolong tea, its flavor is almost that of a lighter black tea. The loose tea is dark brown in color and has a smooth, almost chocolatey taste. Sorry to sound like a pretentious tea sommelier, but I really, really like this tea!

According to a legend, what we now know as Da Hong Pao once cured the mother of an emperor in the Ming dynasty of an illness. Full of thanks, the emperor sent big red robes to cover and protect the bushes from which the miraculous tea had come. This is why the tea, to this day, is called 大红袍 (dà hóng páo), which means big red robe. Some of those bushes that supposedly cured the empress dowager still exist. Tea from those very same bushes fetches exorbitant prices. In the late 90s, 20g of that tea sold for 160,000 RMB at auction. Crazy, right?

You can brew oolong teas more often than their green tea ‘cousins.’ With a good quality tea, 8-10 brews are totally fine.

Oolong teas are best for you (again, according to Chinese medicine) in spring and autumn, but some, like Tie Guan Yin (since it is so light as to almost be a green tea) will be okay to drink in summer. And some, like my beloved Da Hong Pao, can also be drunk during winter weather.

Black Tea

Few people know that China also produces excellent black tea. Actually, what we Westerners call black tea is known as red tea (红茶 in Chinese, hóng chá in pinyin) all over Asia. Where in the West, the color black is used to describe the loose tea, China and other Asian cultures refer to the reddish color of the brewed tea instead.

The best red teas in China come from Fujian, Yunnan, Anhui and Zhejiang provinces. Since tea in China is not drunk with sugar or – God forbid – milk, the original flavors can play out a lot more subtly than with many teas drunk in the West.

A good red (or black, sorry) tea can be brewed multiple times. Like with oolong, 8-10 brews are totally fine. So, if you are not an extremely heavy tea drinker, just one dose of tea can last you most of the day.

Black tea is best for you during the colder months. Of which we, of course, have plenty in Shenyang. So, cheers!

Pu’er Tea

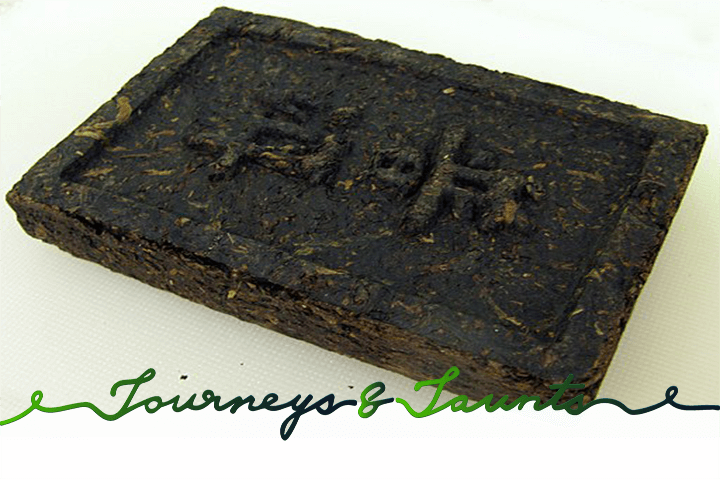

The last variety of Chinese tea I want to introduce to you today is pu’er tea (普洱茶 in Mandarin, pǔ’ěr chá in pinyin). Pu’er tea is fully oxidized and looks completely different from all the other teas we have seen so far. The production of pu’er includes different methods of oxidization or fermentation. Once it has reached the desired oxidized state, the tea leaves are rolled and pressed into various shapes. Most commonly, they will be formed into a round, flattish disc, but there are other popular shapes such as the form of a bowl, a mushroom, a brick or even a square with characters in relief. My friend even has a Chinese ‘painting’ in her shop that is made from pu’er tea.

Tea culture surrounding Pu’er tea is almost as complicated as wine culture is in many Western countries. Pu’er tea comes in two main varieties, raw (生茶 in Chinese, shēng chá in pinyin) and ripe (熟茶 in Mandarin, shoú chá in pinyin).

Raw Pu’er is a tea that was allowed to start its fermentation process, then pressed into shape and left to “ripen” naturally over time. It can be stored for over a century and will become better with age. But, as with wines, a pu’er tea can only improve so much. If the tea was not processed correctly or the tea leaves were not tender enough or came from a young tea shrub, then even aging it for several decades will only produce a mediocre tea.

Ripe Pu’er is a tea that was artificially ripened through forced fermentation with the help of different bacteria and fungi. As a result, it imitates the qualities of a naturally ripened raw pu’er. Usually, one should still let a ripe pu’er mature further for several months or even a year or two, for it to loose any undesired extra tastes it might have acquired during its forced fermentation stage. This tea will improve over time, but should not be kept more than a decade after production.

Tea snobs will argue that this type of tea can never be as good as a well-ripened raw pu’er. While that might be so, some of us just don’t have the time (or patience) to wait a couple of decades for our tea to improve. Or the money to invest in a raw pu’er that has been sitting in a vault for 50 odd years. Speaking of vaults. Pu’er teas are actually a popular investment item in some circles. You buy an excellent vintage year and keep it for several decades, then resell it to the highest bidder. Unless you are thirsty one cold winter night and break into your stash…

Medicinal Tea

In addition to all the varieties of tea above, Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) also makes use of different herbal concoctions and tisanes to cure a multitude of ailments. If you would like me to do another article on those medicinal teas, please let me know via private message or in the comments. I’ll be happy to oblige.

If all of this sounds interesting to you, and you would like to experience the differences between these varieties, why not book a tour with me to spend a relaxing and informative afternoon trying them all? Contact me through julie@journeysnjaunts.com or via WeChat (julie_marx) for more information.