Gansu Province and all of China’s Wild West are places few foreign tourists get to see on their first foray into the Middle Kingdom. More’s the shame, since these locations have much to offer the intrepid traveler. One of my favorite sights in all of Gansu would have to be Mogao Caves. Any history, art, literature or theology nerd will have to agree, I’m sure.

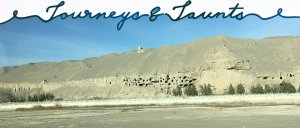

The Mogao Caves (莫高窟 in Chinese, mò gāo kū in pinyin) are located about 25 km outside the town of Dunhuang. These caves – there are a total of 735 hewn into a sheer cliff face – can be divided into two sections. The longer one, located on the south end, contains 487 caves, most of which are filled with stunning paintings and impressive Buddha statues – they have a wealth of history to share with us.

The shorter North Section contains the remaining 248 caves, but they are desolate and in ruin. The sun, the wind, and frequent sandstorms have tried to erase every trace of culture within. This makes the excavation work there – ongoing since 1988 – very hard on the researchers from Dunhuang Academy.

Endangered Art

The South Section, however, has been conserved and offers us glimpses of the history of Buddhism in China through the ages. Unfortunately, because the Mogao Caves are such a big tourist magnet, the treasures within are in danger.

While access to the caves is restricted to a maximum of 6,000 visitors per day, the constant coming and going takes its toll on the artwork, with paint oxidizing and deterioration accelerating. So, if you want to see this beautiful testament to Chinese religious culture, you should go there soon, before it is closed to the public.

Discovering the Caves

Out of the 487 caves of the South Section, only a couple of dozen are open to the public. There are different ticket prices which determine the number of caves you can see on a tour (no one is allowed into the scenic area without a tour guide). But let’s look at mundane aspects like ticket prices later. First, come discover the art!

Layout and Shape

Most worshipping caves have the same basic layout, with an anteroom, a corridor, and the main body of the cave. Shapes of the caves, however, can differ significantly. Some caves’ main roomsare square, some rectangular, depending on the position and size of the Buddha contained within.

Earlier caves, such as those carved in the Western Xia dynasty, often maintained the Indian custom of building a platform for the Buddha that believers could walk around to worship. Caves from later periods tend to have the platform of the Buddha in the front, with a square or rectangular area before it where worshippers stood, allowing for more people to view the Buddha.

Some caves, such as cave 96 – with agiant lying Buddha statue inside – were privately-owned and for the sole use of the donor and his family. That’s opulence for you!

Art from Different Dynasties

Caves shown to tourists are all ones initially used for worshipping Buddhas, as those are the most representative with painted walls, altars for statues, and sometimes stupas. The tour guides at Mogaodo an excellent job pointing out the different painting and carving styles which mark the caves as being from various times throughout Chinese history.

Backgrounds Show the Cave’s Age

Earlier caves, from the Western Xia period, for instance, show cruder landscapes in the background. From the Tang dynasty onwards, paintings contained more opulent, detailed depictions of lush greenery.

At the same time, the artists adapted the stories of the sutras, making protagonists more Chinese looking and incorporating local practices and customs.

Bodhisattvas Changed Their Gender

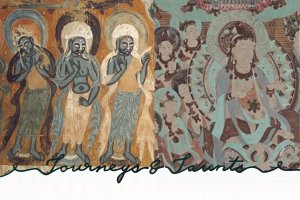

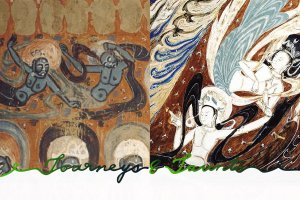

The figures depicted, especially the bodhisattvas and apsaras (菩萨 and 飞天 in Chinese, pú sà and fēi tiān in pinyin) also betray their time of origin. Both bodhisattvas and apsaras are of course concepts from India. But, as time wore on, the Chinese made them their own.

The bodhisattvas (a person on the way to Buddhahood, but has not attained it yet) are always shown as male in Indian theology. Chinese artists started outfitting them with more and more female-looking adornments, though. This made sense, because the bodhisattvas, Guanyin in particular, were seen as mother figures who granted wishes and helped people out in various aspects of life. So, having them be female was a logical choice.

Apsaras Became More Demure

The apsaras (flying beings, often playing music, sort of like angels in Christianity) went from strong, half-naked female figures to lithe creatures swathed in long-sleeved, flowing garments with trailing scarves. This catered to the Chinese sense of modesty and enabled artists to show off their skills at the same time. The supple bodies and swirling clothing were a greater challenge to paint than the naked upper bodies of the Indian apsaras.

Today, the Apsara is the symbol of Dunhuang, and the city is awash with statues and pictures of them. You can buy 飞天 in the form of postcards, figurines, on various articles of daily use, or admire them on house facades, lampposts, street signs, etc. And if that is not enough for you, why not stay at the Feitian Hotel? Or buy from the Feitian Market? Stroll down Feitian Street? All of that is possible in downtown Dunhuang.

The Library Cave

The most special cave (in my humble opinion) in the entire Mogaocomplex is a small and nondescript one – the so-called “library cave.”Branching off a bigger room and walled up for centuries, this cave was discovered in 1900 by a resident Taoist monk.

Oh, you are confused what Taoists were doing in a Buddhist monastery? As trade through the Silk Road declined in the 14th century, Dunhuang fell into obscurity, and the Mogao Caves were abandoned. By the late 1800s, Taoists had repurposed the complex for their own use, restoring and opening up some of the caves to live and worship in.

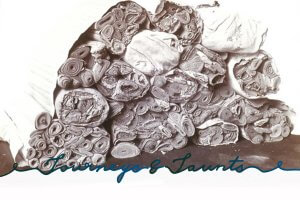

Be that as it may, this particular Taoist monk – named WangYuanlu (王圆箓 in Chinese) – found a crack in the side wall of a corridor he was put to sweep. He opened up the chamber behind it and discovered 50,000 manuscripts in various languages. This find has helped scholars around the world rewrite the history of the Silk Road. They are also invaluable sources for researchers in fields such as history of mathematics, history of musical theory, theology, and more.

Why scholars from around the globe? Monk Wang was rather commercially-minded and sold off a large portion of the manuscripts to foreigners starting in 1907. The first one to pick over the texts and take many of them (along with statues and other artifacts) out of China was Hungarian-born British scholar Aurel Stein. Second in line was French Sinologist Paul Pelliot, followed by Japanese, Russian and Danish explorers.

To date, only about 8,000 of the original 50,000 pieces remain in China. The others are kept in academic institutions around the world, such as the British Library and the BibliothèqueNationale de France. Thanks to technology, digitalized versions of the manuscripts are now freely available online. This way, scholars can study them, regardless of location.

The Mogao Caves Museum

Examples of the manuscripts still in China can be seen in the fabulous Mogao Caves Museum. While many are in Chinese, some are written in Tangut (official written language of the Western Xia dynasty in Gansu), Tibetan, Uyghur, Mongolian, Sanskrit, and other languages.

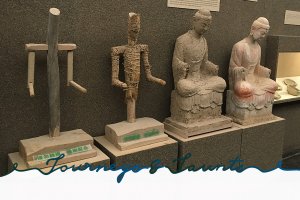

The museum also shows other artifacts found in the Mogao Cave complex and explains (in fabulous English, I might add) the meaning of the finds. From them, we can learn an enormous amount about how the caves came to be, who lived and worshipped in them, and also when they were abandoned.

According to this part of the exhibition, the earliest caves at Mogao were hewn during the Sixteen Kingdoms era (304-439 AD), as there are meditation caves similar in structure and form to caves found in Xinjiang dating to that era. And a manuscript recovered from the Northern Section dated to 1293 AD proves that the caves were abandoned at some point after that date.

But the more substantial part of the museum is dedicated to explanations about the restoration work, the life of the researchers there, as well as an overview of all the “diseases” that have befallen the cave paintings over time and how to remedy them. Since everything is described in English, you should go check it out for yourselves – it is really worth the trip!

The last part of the exhibition consists of life-size replicas of several of the Mogao Caves. Explanations are only in Chinese, but seeing the paintings and statues inside is cool even if you don’t read the language.

Ticket options

As mentioned earlier, access to the Mogao Caves (and the museum) is limited, and tourists need to purchase either a C, a B or an A ticket package. Here is an overview of what these options contain.

With a C ticket (the cheapest version at 50 RMB), you only get to see two movies with explanations about the caves. The first one sets the scene of how Mogao Caves were built. Dashing horsemen, camel caravans, fighting, the backbreaking labor of carving out the caves, this movie has it all. The second one, shown in a 360° theater, introduces some of the caves not open to the public with computer animations. There are audio guides available to go with both films.

Purchasing a B ticket gives you access to the museum with replicas of some of the caves, and explanations of the conservation efforts made, as well as a glimpse of 4 of the caves which can be viewed by tourists. It only lets you stand at the entrance of the caves, though, and listen to the guide’s explanations via loudspeaker. This type of ticket costs 100 RMB per person and is mainly available to Chinese-speakers, who can join a big tour group.

An A ticket enables you to visit 8 caves (and even 12 in the winter, when tourists are few) together with a dedicated guide. It also contains a screening of the two movies mentioned before and lets you see the museum. Since there are not nearly as many English-speaking tourists visiting Mogao Caves as Chinese, you might have the chance of joining a small group instead of the 20-30 people that follow the Chinese-speaking guides around. We were only 4 participants, 3 Laowais and a Chinese friend. Plenty of time for further explanations and questions. This ticket category is 238 RMB with a foreign language guide, 218 RMB for guides who only speak Chinese.

If you want to see extra caves, you pay 150-200 RMB per person for each additional cave you visit. I have not tried this option, as I would rather invest the money in a book with further information on the caves with professional photographs. Plus, the replicas of the caves in the museum are a decent source of information as well. A good guide will also be able to translate the signs at the entrance of each replicated cave there.

If you would like to experience this wonder of Chinese history before it closes, Journeys & Jaunts puts together bespoke itineraries for travel to Gansu, including Dunhuang and the Mogao Caves. We can also help you book entrance tickets, hotels, and make travel arrangements.