Zhang Zuolin – lovingly nicknamed the “Old Marshall” by the Chinese and a major figure in the national history of China – is an unknown entity to many in the West. Here in Shenyang, we are lucky in that we have not one, but two different museums dedicated to him.

One of those is Commander Zhang’s Mansion – the palace-like manor complex he started building for his clan in 1916. And the second one is the Huanggutun Incident Museum, which talks about his life and death and places both in the greater context of Chinese history at the time.

The incident after which the museum is named refers to a bomb planted by Japanese soldiers that blew up the train in which Zhang Zuolin traveled from Beijing to Shenyang. The Old Marshal died from the wounds received in the blast and after his death, his son Zhang Xueliang took over governance of China’s Northeast.

This free museum is an oft-overlooked gem in Shenyang’s Huanggu District. So let’s get an overview of what it contains, shall we?

How to get there?

The Huanggutun Incident Museum(click here for the pin) is located on Tianshan Road 207 (天山路207号 in Chinese, tiānshān lù 207 hào in pinyin) in Huanggu District. None of the subway stations are really close, but buses 112, 190, 海逸铭筑支线 (hǎi yì míng zhù zhī xiàn in pinyin), and 预备役号专线 (yù bèi yì hào zhuān xiàn in pinyin) all stop right there. Taking a DiDi or a shared bike from the subway (岐山路 or qí shān lù in pinyin is probably closest) might be an alternative. If you have the luxury of owning a car, driving there is another option.

The museum is open Tuesday through Sunday from 09:30-15:30. Like so many museums in China, it is closed on Mondays.

Entry is free of charge, but the museum staff ask that all groups of more than 20 people register ahead of time, to make sure that there are no other large groups that same day.

When you enter the museum

The Huanggutun Incident Museum is housed in the old station house of Huanggutun train station. When you walk in, you are greeted by a large mural depicting the train station as it would have been in the 1920s, complete with some travelers.

Another mural shows the scene right after the Huanggutun Incident, with police on the scene of the explosion.

You also get to see a model of the station house, along with some very interesting details (like the washing drying on a clothes line and some trash on the roof of one of the buildings).

The explanations in the museum are all in Chinese, only a very limited number of things are available in English. But many of the pictures and maps are easy to understand. And if you feel you need more in-depth explanations and/or translations of the captions, why not book a tour with Journeys & Jaunts? Write us a message through the WeChat account or send an email to julie@journeysnjaunts.com for a quote and to find out available dates.

From simple soldier to country leader

The picture gallery with explanations in the first show room describes Zhang Zuolin’s origins and his rise from a poor boy from the Western part of what is today Liaoning Province to the leader of China (if only for a short period of time).

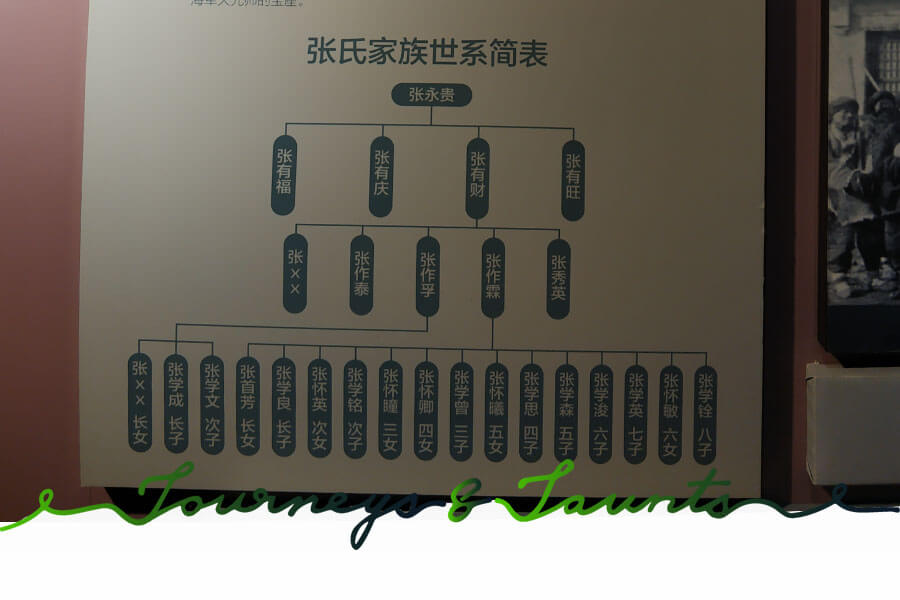

A family tree shows where he came from, and – more interesting, at least to me – the numerous offspring from his six (!) wives.

Old photographs show important figures in Zhang Zuolin’s rise to power – from when he entered Shenyang (then called 盛京 or 盛(shèng)京(jīng) in pinyin) to when he annexed today’s Heilongjiang and Jilin provinces.

Other shots show him and others involved in the First and Second Zhili-Fengtian Wars and Guo Songling and his opposition to Zhang.

You have to love Zhang Zuolin for his fashion sense alone. The elaborate uniforms he favored and even dressed his sons in are something to behold.

Origins of the conflict with Japan

The next part of the collection describes how the Japanese first came into China’s Northeast. Again, pictures and maps of troop movements illustrate this part of Chinese history.

One of the things enabling Zhang Zuolin to become as powerful as he did was that he could leverage the industrial strength of the Dongbei region. Investments by the Japanese led to Zhang Zuolin being master over 90% of China’s heavy industry and becoming one of the richest and most powerful warlords of the era.

Knowing where his wealth stemmed from, Zhang kept strong ties with the Japanese. At the same time, he also sought contact with Western countries.

But the Western powers were otherwise engaged when World War I broke out and Japan seized the opportunity to extend its influence in China. They forced Chinese president Yuan Shikai to sign a treaty giving them more access to land and more rights. This is seen as an unequal treaty and ‘selling out China’ by some historians.

Chinese citizens rallied and started fighting against the Japanese, not just in the Northeast, but all over the country.

Background of the Huanggutun Incident

The next part of the exhibition discusses the first time the Japanese tried to kill Zhang Zuolin (whom they felt was getting difficult to manage), which was in 1916. The Japanese put together an “assassination squad” that was supposed to murder Zhang Zuolin, but ultimately failed in its endeavor. There are light boxes that let you follow the entire thrilling episode.

The museum also gives an insight into the so-called Zhengjiatun Incident (郑家屯事件 in Chinese, zhèng jiā tún shì jiàn in pinyin), which is a horrifying story of how a child spitting melon seeds at passersby can turn into bloodshed between the armies and police forces of two countries.

The collection of reproduced photographs and documents further elaborates on the changes in the relationship between Zhang Zuolin and the Japanese, such as through the two 东方会议 (dōngfāng huì yì in pinyin, roughly “Eastern Conferences” in English), which led to a deterioration of Sino-Japanese ties.

The Huanggutun Incident

The next part of the exhibition finally deals with the namesake of the museum – the Huanggutun Incident. We get detailed information on how it was planned, including how the spot for hiding the bomb was chosen, who was on the “planning committee”, to which building the plan was hatched in. Then, the journey that took Zhang Zuolin back to Shenyang is described, along with who his travel companions were.

For an even more immersive experience, head to the projection room every hour on the hour between 10:00 (first showing) and 15:00 (last showing) to see a multi-media clip about the incident.

I love the way they have depicted the incident through so many different media. There is a big diorama with “photographers” of the time busily snapping away. There are photographs showing the scene as it was then. And there is the abovementioned clip that you get to experience at the projection room.

The aftermath of the incident is represented by clay figures of Zhang Zuolin’s 5th wife, who pretended to the wife of the Japanese Consul that Zhang was alive and well even after he had already passed away from the injuries sustained in the blast.

On the reproductions of old photographs, we get to see Zhang Zuolin’s funeral.

The museum also gives an overview of how the Huanggutun Incident has been reported throughout time. A lot of the actual story stayed hidden for decades. Most of it came to light when the Japanese soldier who was responsible unveiled his story to the media in the 1950s and co-wrote a book about it.

The aftermath of the Huanggutun Incident

In this part of the museum, we learn about what happened after Zhang Zuolin’s demise. First, it describes how his son Zhang Xueliang (nicknamed the “Young Marshal”) took over the reins and the state of China’s Northeast as a result of that change in power.

It highlights the collaboration between Zhang Xueliang and Chiang Kai-shek and depicts the Young Marshal taking over the command of the army of the Republic of China.

The pictures and captions give a brief overview of several incidents that played important roles in politics at the time – especially the Nakamura Incident and the 9.18 Incident. Another cool multi-media presentation in this part of the museum lets visitors discover the major figures implicated in the Huanggutun Incident.

Museum gift shop

The last room of the museum is filled with traditional Chinese handicrafts. If you are visiting the museum and happen to look for some of Liaoning’s intangible cultural heritage, you could just pick up a piece or two here.

They have red paper cuttings, leather shadow puppets, calligraphies, Chinese paintings, and much more.

Outside Area

This is it for the museum. But once you have left the building, do not run away immediately. Outside, there is a life-sized replica of the train Zhang Zuolin was traveling in, as well as bronzes depicting people in clothes from the 1920s.

And also plenty of old photographs. It is fun walking along the wall showing them and trying to figure out where in modern-day Shenyang those places are!

Hopefully, the introduction to the Huanggutun Incident Museum has made you even more curious to see this hidden gem of Shenyang culture in person. If the prospect of slogging past walls and walls full of Chinese characters trying to guess the meaning is daunting, come book a tour there with Journeys & Jaunts. Contact us through the WeChat account or send an email to julie@journeysnjaunts.com for details.

That email is also where you can sign up for the free weekly Shenyang newsletter with events happening in the city.